Saturday, September 29, 2012

Current Sentinel Literary Quarterly, Sentinel Nigeria and Sentinel Annual Poetry & Short Story Competitions

Prizes: £150, £75, £50, 3 x £10

Entry Fees: £3 for 1 poem, £11/4 poems, £12/5 poems.

Judge: Andy Willoughby

Closing on the 30th September 2012

http://sentinelquarterly.com/competitions/poetry-0912/index.htm

Sentinel Literary Quarterly Short Story Competition (September 2012)

Prizes: £150, £75, £50, 3 x £10

Entry Fees: £5 for 1 story, £8/2 stories, £10/3 stories, £12/4 stories.

Judge: Jeremy Page

Closing on the 30th September 2012

http://sentinelquarterly.com/competitions/short-stories-0912/default.html

Sentinel Nigeria All-Africa Poetry Competition (November 2012)

Open to all professional and amateur writers from Africa living within or outside the continent. Prizes: N35,000.00, N20,000.00, N10,000.00, 3 x N4,000.00

Entry Fees: N450/£2.50/$3.95 per poem.

Judge: Chiedu Ezeanah

Closing date: 30th November 2012

http://sentinelnigeria.org/online/sentinel-nigeria-all-africa-poetry-competition-november-2012/

Sentinel Nigeria All-Africa Short Story Competition (November 2012)

Open to all professional and amateur writers from Africa living within or outside the continent. Prizes: N35,000.00, N20,000.00, N10,000.00, 3 x N4,000.00

Entry Fees: N450/£2.50/$3.95 per story.

Judge: Jude Dibia

Closing date: 30th November 2012

http://sentinelnigeria.org/online/sentinel-nigeria-all-africa-short-story-competition-november-2012/

Sentinel Annual Poetry Competition 2012

Open to all.

Prizes: £500, £250, £125, 5 x £25

Entry Fees: £5 per poem for the first 2 poems, £3.50 per poem thereafter.

Judge: Roger Elkin

Closing on the 30th November 2012

http://www.sentinelpoetry.org.uk/sawc/2012/poetry.html

Sentinel Annual Short Story Competition 2012

Open to all.

Prizes: £500, £250, £125, 5 x £25

Entry Fees: £5 per story for the first 2 stories, £3.50 per story thereafter.

Judge: David Caddy

Closing on the 30th November 2012

http://www.sentinelpoetry.org.uk/sawc/2012/short-story.html

Friday, September 28, 2012

O Lord won’t you buy me an iPhone 5?

My mobile life is in crisis.

Since Orange merged with T-mobile, the signal in my area, on my primary cellphone, has ranged from crap to shit.

Add to that the instability of the BlackBerry [Is RIM gonna stay in business or quit?] and you get an idea of what's eating me.

The Nokia on 3 Network often can't find 3 at all. It keeps saying SIM registration failed. So I am stockpiling minutes I can only use outside my home. How useful is that?

The strange thing is that the Lebara phone I got for calling Nigeria, and also for finding out who's flashing me from Naija is the one phone that has full signal bars all the time, but with the free minutes being for Lebara-Lebara calls only, and I don't know more than 2 people on Lebara, this phone is only good for calling Nigeria. It serves no other purpose in its life.

And the son of Isuikwuato man is stuck on them bastard contracts until middle of 2013. 'Tis an ef'd-up mobile life true true. Haba mana!

O Lord won't you buy me an iPhone 5 on Vodafone, Please? All my neighbours on Vodafone don’t complain of poor signals. From all indications, I’ll have a longer mobile life eating an Apple than many Blackberries.

- Nnorom

Wednesday, September 26, 2012

Cat or Catfish?

He doesn’t want anyone to think he has lost his mind. It might only be a dream, but there is a school of thought that believes dreams to be the manifestation of a man’s true world. Just to be safe from unwanted questions, he writes on his Facebook page:

Does anyone here interpret dreams? Interpret this:

A man walks into a restaurant and orders a plate of white rice and fried plantains. The waitress ask him what kind of meat he would like.

"Cat" he says nonchalantly.

The waitress is perplexed. "You mean catfish?" she manages to ask.

"You asked what kind of meat I wanted. Didn’t you? Cat, please." He is now a little irritated.

"As in pussy cat?" the poor waitress asks again.

"Yes, you little witch, cat, as in pussy cat; with all the meows and whiskers. Are you deaf?".

“Oh my God!” She vomits on the restaurant floor, drops her tray and runs out of the restaurant, crying violently.

Just then the bedside alarm shrieks. He is relieved to find himself in his own bed, and not in a restaurant with tens of disgusted eyes gutting him. It is 2:00am. He gets out of bed and pats himself down with some concern. His shirt is wet through and through with sweat - on one of the coldest nights in Britain.

***

If your friend told you he had this dream, what would you tell him?

He puts on the kettle and waits for the interpretations to start coming through.

- NNOROM AZUONYE

Tuesday, September 25, 2012

Build Africa Poetry Competition, 2012, Results and Judge’s Report

The winning poems for the 2012 Build Africa Poetry Competition are as follows:

First Prize: Understanding Dung Beetles by ROGER ELKIN

Second Prize: Artichokes and an Olive Grove by MANDY PANNETT

Third Prize: Stalkers by FAY MARSHALL

Two other entries have been selected as ‘Highly Commended’ from a strong list of poems also deserving of such honour. The two highly commended poems are:

1. Titania’s Wood by MANDY PANNETT

2. Finding Edna by BRUCE HARRIS

Congratulations to the winners. The winning and commended poems will be published in the Excel for Charity News Blog on the 1st of October 2012.

This competition has raised £69.48 for the Build Africa charity. Thanks to all the entrants.

Now here is the Judge’s report:

Report on the Build Africa Poetry Competition, 2012

Judgement in literary competitions is burdened with the expectation of precision in the determination of value. It is of course also burdened with the challenge of perspective. Added to this is the paucity of material a judge or any critic has to work with in determining the relative strength of poems. A novel or short story presents the critic or judge with more material, many pages of information, by which it can be evaluated against another novel or short story. Prose-fiction does have its own challenges, but it comes with significantly less unresolved ‘tribal’ conflict than poetry. The poetry universe is seriously sectarian, with factious practice camps, which sometimes refuse to publish, honour or even acknowledge each other. This does inform judgement in a poetry competition.

Perhaps, I exaggerate, or hope I do, hope indeed there is greater agreement on value between differently persuaded poetry practices and traditions. It may be that the greater quarrel is about form rather than value, though the two issues tend to be conflated. So, if we like a certain kind of poetry we happily attach value to it, but if we are not happy with that way of writing poetry we do not even care that it may be of significant value to others. We just don’t touch that kind of poetry, won’t buy or read it unless we have professional interest in it – as would media reviewers, academics, archivists and other collectors.

The good news for those who support and enter poetry competitions is that the qualities by which the best poems succeed and excite interest remain unchanged and roughly same across the tribes. To an extent the bickering of our poetry tribes has complicated perceptions of value and capacity for fairness in judgement, but excellence is ultimately its own way maker, and poems which emerge winners will usually be among the best of any kind in practice. A poem is only fairly judged according to its form – the extent to which it excels in the appropriation or exposition of those qualities germane to its form. If we understand what a poet is doing in a poem we can determine how well he or she has done it, and also accurately compare the quality of what has been done to what other poets have been able to do working with the same material in a similar manner. If we are informed enough through training or practice, or just as experienced readers, we can also judge correctly that a given poet has done more or less excellent work with a chosen set of poetry material than another poet working on a different set of material. In judgement, it helps to be informed by the history of practice and the movement of innovation. No poetry competition is judged in an ahistorical vacuum.

I was thus mindful of our poetry moment, its centred practices and attendant politics of placement, coming to the 2012 Build Africa Poetry Competition. I decided to begin as I intended to conclude, by examining and moderating my own preferences and perspectives. In the end I was able to find clear winners from my shortlisted entries, but I think it is useful to generally remind those who win a poetry competition and others whose poems only made the shortlist that the values of the governing poetics in a competition can in some cases determine the outcome. The triumph of the winners will in such cases represent excellence but also good fortune, especially where there has been performance parity or something close to that among the best entries. For the winners there ought to be joy in the public acknowledgement of excellence by peers, delight with progress in craft, but scant room for triumphalism as in sports competitions.

What kind of poems was I hoping to find and honour in the 2012 Build Africa Poetry Competition; that is, what baggage did I come to this judgement with? I find value in all poetry forms and traditions. I like to go beyond the centred poetics of dominant perspectives in recent poetry publishing and creative writing education, and find value in whatever form it is being offered. Every kind of poetry is capable of excellence but not every poem is excellent. I do not insist on showcase poems, the kind that scream ‘Look at us! We are poems!’ at every reader, but I have retained that healthy foundational interest in ambition, eloquence and the personal voice in practice. Poetic difficulty is not for me just a period modernist obsession because there is even more complexity in the cosmopolitan contemporary, more of everything tied together and still unresolved, to complicate the art and unconscious of practising poets. I recognise that what I consider ambition in practice – elaborate or exceptional exploration of craft or subject – some now see as pretentious. However, I still believe in the thinking poet’s poem and consider elaborate thought, histories and mythologies valuable material for practice even in our time, just as valuable as the preferred autobiographical realism of the snap shot here and now, recorded ad nauseam in recent narrative poetry. I worry about poets being the inescapable protagonists of all or most of their poems, but recognise and respect the fact that this is essential fare for much recent poetry. It happens with poets for whom practice is not only art but also confession and therapy.

I hoped to find in these competition poems a settled ownership of language, confidence in the application of meaning, because in most cases poetry practice still involves the creative processing of meaning, demanding or demonstrating above average dexterity in the verbal arts. You have to own or know enough of language before you can successfully ‘disown’ it, or attempt to deny it meaning or even presence in your work as some poets have done and some still do. I wanted to encounter the competition poems first as a lay or ‘common’ reader, and so expected to be provoked, informed, entertained, inspired and humoured, becoming so moved by whatever I read that I would want to read it again… possibly pick up a poetry reading habit if I wasn’t already one of the converted. I was looking for variety and strong individual voices. I hoped the competition would provide in its variety the lyrical and narrative, even commentaries of compelling descriptive and expository power. Poetry is all of these things. It embraces all subjects, nothing off limit or taboo.

Thankfully, I did find the variety and robust poetics I was hoping for in this competition. The winning poem, ‘Understanding Dung Beetles’ is not for the squeamish, but the poem’s conversational tone and humour draws its readers to share an interest in what will be for many an unusual and possibly unsuitable subject. For both poet and readers, there is hard work in this informative poem, involving the processing of specialist information, but this is neither obvious nor obtrusive because the poet has masked it with an informal tone, that near conspiratorial voice by which the subject is exposed. In the third stanza there is the kind of heady information on dung beetles by which the poem is mostly constructed:

They work arse-over-heels, literally:

though have spade-shaped heads

use their hind legs to shift a dung ball

fifty times their body weight: backwards.

There is more rib-tickling erudition in the poem from where that came. But there is also a serious purpose to all that laughter. We get to know the dung beetle, get to know the importance of its life to our lives, and are moved to serious thought, as the poet in conclusion:

Dung is all they own.

Get high on piles of ordure.

And dedicating their lives to dung

question the testament

that bread is the staff of life.

We are on a journey in ‘Artichokes and an Olive Grove’, second prize winner in the competition. It does not matter so much that this journey may be more imagined than real. What engaged me as a reader was how the poem enacts movement as metaphor, imagining progress from brokenness and despair towards hope. There is a Mediterranean theme in the references to Laertes, a name from Greek mythology, and the two land products, artichokes and olives, from which the poem takes its title. The allusion to Greek mythology, in particular Homer’s Odyssey, informs the poem’s interest in place or land as a cathartic as well as therapeutic site for the processing of personal journeys, connecting the past with its present and possible future –physical and emotional journeys of acceptance and closure, recovery and renewal. The quiet, persuasive voice of the poem is speaking life or healing or hope to one slumped “like an over-blown poppy” on a donkey of despondency. Instead of staying saddled to that ‘donkey’, or removing to an ‘island’ location, an Odysseyan quest land, only to relive the pain of loss and separation, hope was on offer at a land of new beginning, a restful upland location, with familiar or reassuring olive surrounds, from which to look beyond the moment:

In those hills is an olive grove

and a plot of land to grow artichokes on

where we shall put that donkey out to graze.

This rich poem has a simple lineal structure, moving from the observation which identifies its conflict early in the first line, ‘’Your spirit slumps in the saddle’’, to the two questions which engage and then resolve the conflict: ‘’What can I offer to make you look up’’ and “A small farm then, in the backhills?’’ A concluding observation completes the frame, identifying resolution of the conflict with the line, “You are starting to un-slump”.

I liked the ambition of these first two winning poems and the risks successfully taken in the choice of subject, the referencing of mythology, and use of detail, including scientific data. Mood is a significant contributor to enrichment of reader experience in both poems. ‘Stalkers’, winner of the third prize, as well as ‘Finding Edna’ and ‘Titania’s Wood’, which I highly commend, all demonstrate this impressive use of material, as do a number of other poems. ‘Stalkers’ wins the early interest of its reader by suggesting itself as a detective story. We immediately want to know who the stalkers are, a question the poem only responds to tangentially but never quite answers. Instead it provides descriptive identikits to guide its readers towards own interpretations and conclusions on who the culprits might be – as in police artist drawings of unknown villains:

The first

is a handsome brute;

……………………….

it swoops from tree-top to tree-top,

hurdles roads, blazes across horizons,

ravager, turning

forest to ash, cropland to desert

Looking at this portrait, we may begin to sense that rogue weather types and ecological disasters are the enemies we seek here rather than human or animal agents, but this is inconclusive. So we seek further information by turning to more of the pictures:

The other stalker

is more insidious.

It sleeks beneath sills in serpentine coils,

undermines drip by slow drop,

fragile foundations;

inches up imperceptibly,

sinks islands,

swamps cities;

swallows shores

Aha! We think we are now sure about these stalkers, and even if we still don’t know who or what they are we are happier for taking part in the adventure the poem has provided.

It has been a pleasure reading these poems – all the competition entries. I found in them much comfort, and the support to continue celebrating poetry in all its subjects, forms and traditions. I hoped to find excellence in its various poetry signatures and did. I hoped to find boldness in the use of language, adventure in the application of form, and I did too. I would say it has been a successful outing for the Build Africa Poetry Competition and its organisers.

Afam Akeh

Oxford, UK.

Tuesday, September 18, 2012

How to get people to love you and even mourn your car.

(For Elnathan John)

Let’s face it, the average human being assimilated by Facebook now has an average of one thousand smart philosophical opinionated friends.

The average member of the human family no longer has time to love another human being or thing. Facebook does not help matters with that bloody ‘like’ button. It now happens that somebody announces the death of his father and he receives a thousand alerts; ‘this person and nine hundred and ninety-nine others like this.’ What do they like? The news of the dead father? People don’t even know what they like and certainly don’t give a flying you know what about anybody.

But it does not have to be so. You can actually get people to love you and love the objects of affection in your life. It is very easy to be honest.

First, you take a name like Elnathan John. The choice of names is extremely important. The name must not sound Nigerian. Who the hell is going to trust you if your name is Onetoritsebawoete, Otagburuagu, Olufanikayode, Mustapha, or Aniekanabasi? Are you kidding me? There is a reason Nigerians themselves believed their luck when somebody named Goodluck Jonathan asked to become their president.

After that most important step of choosing an international name, the next thing you do is make friends with two very important people. One of them should be somebody like Ike Anya. He is a public health consultant in Great Britain. Great Britain! He is a well-loved person. He has a squeaky-clean image even if he is not clean-shaven. He has integrity. Make sure people know Ike Anya is your friend. Then go across to the United States and find a middle-aged mirth merchant consumer of books. This must be a man that people love to hate and hate to love at the same time. He should have a name like Ikhide Ikheloa; no respecter of person or office. He says things they are. Nobody gets enough of this marmite of a man. You either love him or hate him. Make sure people know Ikhide Ikheloa is your friend.

Having secured the name and fortified yourself with these friends, you must then begin to take different segments of the society and open their behinds in the pages of a national newspaper. Spare nobody; Nigerians seeking Asylum abroad, religious worshippers, opposition politicians, Nigerian writers, Nigerian mechanics etcetera etcetera. When you write about any of these groups, keep it honest, so that nobody will have a reason to attack you. Keep it funny. People are less likely to hate you if you make them laugh. Keep it short and sweet and before people get a chance to tackle you, move on to another group and open their big Nigerian behinds in the pages of a national newspaper.

If you follow these simple rules, people will love you and if for any reason you get into an unfortunate accident and your car gets written off, all your friends, even those who do not believe in God will pray to God to get you back to serving your much-loved tonic. They will even shed tears for your car.

- NNOROM AZUONYE

Wednesday, September 12, 2012

‘From my bedroom in London, I created a brand that has sold Nigerian literature to the world’ - Nnorom Azuonye, publisher, Sentinel magazine

This interview by HENRY AKUBUIRO was first published on Sunday, 21 March 2010. (Reproduced in The Blogazette for archival purposes)

Nnorom Azuonye is the Founder and Administrator of Sentinel Poetry Movement, Editor of Sentinel Literary Quarterly, and Publisher of Sentinel Nigeria magazine. He is the Director of Operations and Creative Services, Eastern Light EPM International and Administrator of Excel for Charity International Writing Competition Series. Author of Letter to God and Other Poems (2003), The Bridge Selection: Poems for the Road (2005) and Blue Hyacinths (ed. With Geoff Stevens, 2010), his poetry, fiction, essays, and interviews have appeared in various international anthologies and journals including, For The Love of God (Desmond Kon et al. eds. 2004), DrumVoices Revue, Agenda, Flair, Keystone, Poetry Monthly, Orbis, Ink Sweat and Tears, African Writing, Maple Tree Literary Supplement, and Swale Life, among others. In this interview with National LIFE, he talks about his efforts in transforming new Nigerian writings, among others.

Excerpts:

The Sentinel Movement kicked off from England back in 2002. What informed its birth and to what extent has the founder’s dreams been actualized?

I started Sentinel Poetry Movement from my bedroom in Anerley, South East London on the first day of December, 2002. It was a step forward from my personal website nnoromazuonye.com where I had featured guest poets Nathan Lewis, my brother Kodi Azuonye, an Abuja-based attorney and poet, and my former lecturer, Esiaba Irobi. By the time I featured Irobi, I realized, and with his encouragement, that what I was doing on my website was bigger than my site, hence the registration and launching of Sentinel Poetry Movement. Obi Nwakanma was my first guest poet in December, 2002. The idea was simple: to build an online international community of writers, to provide publishing opportunities for writers from every part of the world regardless of race, age, gender or sexuality and to provide a platform for Africans in particular to get their voices heard alongside international writers. These objectives have been well realized. Over the last seven years, Sentinel has published writers from all over the world, including Kangsen Feka Wakai, Femi Osofisan, Gabeba Bederoon, Jim Bennett, Adam Dickinson, Emmanuel Sigauke, Idris Caffrey, Armand Ruffo and Roman Graf, to mention a few out of the hundreds.

Back in the days, literary journals have led to discovering and celebrating great Nigerian poets/writers. Has Sentinel made this possible in this age?

I can confidently claim that Sentinel has been a strong capital in selling Nigerian writers to the international community through our online and print publications over the years. Tolu Ogunlesi is one of Nigeria’s best known writers today. Sentinel did not discover him, but we were one of the first journals to recognize his talent and publish him in both our print and e-journals. His poem, “Abeokuta,” was picked up for note in a New Hope International independent review of Sentinel Poetry Quarterly in 2004. Afam Akeh, who has been writing forever, has graciously told me that the Sentinel expedition has been very instrumental in reviving his writing. But I will be hard-pressed to find a Nigerian writer actively writing in the last decade who has not been given a platform on Sentinel. Those whose works have not been published by us, have had their works reviewed or appreciated in a Sentinel publication. “Achebe’s Poetic Drive”, the seminal essay by Obiwu that tackles the concept of Achebe as a poet and his poetry, was first published in Sentinel Poetry Quarterly, for instance. We have published Nigerian names and works your interview space will not take, from Aminu Mahmud (Obemata) to James Agada, Kola Ade-Odutola, Chiedu Ezeanah, Victoria Kankara, Chika Unigwe, Chika Okeke-Agulu, Obiora Udechukwu, Kunle Shittu, Tade Ipadeola, Toni Kan, Aniete Isong, Uche Peter Umez, Sanya Osha, Victor Ehikhamenor, Ikhide Ikheloa and Emman Usman Shehu, to mention a few. A minimum of fourteen thousand people use the Sentinel website every month. Note that Ilorin-based poet, Akinlabi Peter, recently won the First Prize and £100.00 in a Sentinel Literary Quarterly Poetry Competition, beating entrants from Australia, United States, United Kingdom and Canada. What we do at Sentinel is provide the platform for literary expression. Any writer we give the exposure to could choose to exploit it or bury his talent. I am satisfied that we do our work well. I am proud of what Sentinel has achieved.

How do you respond to insinuations that Sentinel only publishes “parley” poets/writers to the detriment of those who don’t have friends within?

That is actually a brilliant piece of rubbish. I should not be persuaded to dignify such insipid insinuations that are not based on fact with a response. But then the insinuations are there and you have asked the question. Let me say this: As publisher of Sentinel, I have published such Nigerian writers as Akinbola Akinwunmi, Tope Omoniyi, James Agada, Sanya Osha, Frank Ugoji, Ejevwoke Ophori and James Tsaaior, for instance. These are people I have never met. People that are not on my Christmas list, so to say. Our back list that goes back over seven years has scores of such names that I do not remember. Definitely not my close friends or associates. As a publisher and editor, I am not stuffy and will publish things I like which may not necessarily be orgasmic to the initiated Nigerian writer or critic. Yet I reject a whole lot of work that I deem unacceptable. Many young Nigerian writers don’t take rejection by an editor or publisher kindly. It is, however, the nature of the beast in our industry and they must learn to accept it. I have received insolent e-mails from writers I have rejected their work, and even threats have come once in a while. But when they do, I simply put on the kettle and lose myself in the luxury of Kenco aroma. I laugh and get back to work. I am not surprised people are talking. But that is evidence that we are doing something right.

You took over from Amatoritsero Ede not too long ago. What have you brought to bear on the publication since then?

This will be a little history lesson. Forgive me if I sound a little self-indulgent, a luxury I can only enjoy at times like this when I don’t work within a set form of poetry. I founded Sentinel Poetry Movement and the magazine Sentinel Poetry (Online) and served as its Founding Editor from December 1, 2002 and pretty much set the tone of the magazine. By the close of play in 2004, with so much happening in Sentinel Poetry Movement, including the then boisterous Sentinel Poetry Bar, Expression Warehouse and Open Forum, I also, in July, 2004, started a print magazine known as Sentinel Poetry Quarterly. It all seemed too much for one black man. I looked for somebody to take over editorship of Sentinel Poetry (Online) magazine. I wanted somebody whose attitude to poetry and taste in poetry was completely different from mine. Amatoritsero and I came to an agreement on it, and in February, 2005, he took over. I also implemented an earlier plan suggested to me by Sylvester Ogbechie, to introduce artworks in the magazine. This coming together with Amatoritsero’s purist kind of taste for poetry changed the tone of the magazine. I also brought in Patrick Iberi as Art Editor. With Patrick and Amatoritsero worrying about the magazine content, I concentrated on the actual production of the magazine and we came out with some really amazing editions of Sentinel Poetry (Online) that I am still proud of today.

But things changed. Shortly after I got married in 2006 and my wife and I were expecting our first child, I was not as available for Sentinel as I had been when I was single. Also, the break-in into my home and theft of the main computer I built Sentinel on, made matters worse. I also moved back to London from Dartford after my wife and I experienced some really nasty racist incidents. During this period, communication problems developed between me, Patrick and Amatoritsero. The kind of flawless teamwork we had built, crumbled and for the first time since the establishment of Sentinel, we failed to publish one issue of the magazine. Patrick soon wrote in to resign and so did Amatoritsero. The duo shortly emerged with Maple Tree Literary Supplement with Amatoritsero Ede as Editor and Patrick Iberi as his Art Editor. Again, that is the nature of the beast.

Following these events, I resumed editorship of Sentinel Poetry (online) in December, 2007. At that point, the dynamics of the game changed. Mind you, I had started Sentinel Literary Quarterly (SLQ) in September, 2007. SLQ was a replacement of our earlier title, Sentinel Poetry Quarterly. It just was not feasible for me to continue publishing both Sentinel Poetry (online) and SLQ. Therefore, in October 2008, I merged Sentinel Poetry (online) and SLQ into the single publication that it is today. In my view, and some people may disagree, SLQ has grown from strength to strength. We are publishing more diverse, eclectic, and I hope, stronger literary voices in poetry, fiction and drama. We also run writing competitions with a total prize fund of £400 (Four Hundred Pounds) every three months. Unfortunately, we don’t get Nigerians either in Nigeria or in the Diaspora entering these competitions. The joke is that the first time a Nigerian, Akinlabi Peter, entered the competition, he won. I see the poems that people enter. They range from the ridiculous to the perfect. Some of the best known names in British poetry enter the competition, but they don’t always win. Because the competition judges don’t get to see the names of the authors, they only go with the quality. I suspect that if more Nigerians participated, they would win many of the contests. It is a hard sell though. Pay to enter competitions are not the cup of coffee for Nigerian writers. I was impressed recently when I saw a pay to enter competition run by Abuja Literary Society with entry fees of $20 or so per poem. At Sentinel, it costs only £3.00 per poem to enter.

What led to the birth of the first national chapter, Sentinel Literary Movement of Nigeria?

Ambition. I have this dream of a global Sentinel Literary Movement brand with local chapters in every nation of the world. I dream of each of these chapters telling the stories of their own people through their own local Sentinel magazine. I dream of these visions in the hands of the optimistic young, so that as we, the ageing grist, get rinsed out of the mill, new stars shine in our places and make our accomplishments truly outlive us. I am very pleased that the first national chapter of Sentinel is the Nigerian one. I think that my choice of Richard Ugbede Ali as Administrator is perfect. He presents a ‘can do’ attitude that makes me leap into the air. Nothing kicks that young man, and I think that choosing him to fly Sentinel in Nigeria is one of the best decisions I have made in my life. I am hoping that time will not prove me wrong. I have received many of those e-mails from my people expressing anger at my choice of a Northerner to lead Sentinel in Nigeria. The truth is that I did not and still do not see Richard as a Northerner, I see him as a Sentinel poet who has been a member of Sentinel Poetry Movement and Sentinel Poetry Bar since 2003.

How has it projected the Sentinel cause at home and abroad?

It is well on its way. Sentinel Literary Movement of Nigeria was established in November, 2009, and is set to harness and showcase the Nigerian literary talent inside and outside Nigeria for the appreciation of the entire world. The website: sentinelnigeria.org is already receiving high keyword rankings in major search engines with related searches such as Nigerian Literature, and Nigerian Writing. I reckon that by the end of its first year, it would have achieved a few Sentinel objectives such as providing a publishing platform for Nigerian writers at home and outside the country, building a global Nigerian literary community, instigating productive debates on Nigerian writing and presenting a veritable source of material for international scholars interested in Nigerian literature.

Its associated magazine, Sentinel Nigeria, came into existence recently, what’s the impression/feedback like?

Yes, February 15, 2010, was the day Sentinel Nigeria was first published. It has been a confident debut by Editor-in-Chief Richard Ugbede Ali and his editorial team, including Fiction Editor Kanchana Ugbabe; Poetry Editor Unoma Azuah; and Features Editor Nze Sylva Ifedigbo. I gave them a free hand to publish what they deemed fit and never leaned into them one way or another. I simply published what they presented to me. To be totally honest, I have had mixed feedback from independent assessors of the magazine. Some have praised the new magazine and commended the quality of some of the offerings. Others have said that some of the writings in the magazine were not fit for purpose. It is all in the appraisal report I shall be sending to Richard soon. Good or bad, I am the publisher and I take responsibility. Overall, I give the new magazine a pass mark, but Sentinel Nigeria has so much to learn and a whole lot better to get.

Online magazines are hardly patronized in a developing country like ours. How do you encourage readership, as well Nigerian contributors to be contributing to the publication?

Yes, you are quite right. Many people have already told me that due to the high cost of Internet access in Nigeria, not many who desire it can actually afford to log on and read the magazine. I am, therefore, considering having a digital version of the magazine every quarter on a ridiculous subscription rate of just 50 pence, about one hundred and twenty-five naira only. So that the magazine will be delivered to subscribers directly by e-mail and they can print it out or download to their flash drives and read the magazine offline. At the moment, we are not paying contributors, however from Issue Three of Sentinel Nigeria, my company, Eastern Light EPM, will sponsor four Editors’ Choice awards in Poetry, Fiction, Drama and Essays/Reviews worth £15.00 (Fifteen Pounds) each. Details of this will be available on the website as soon as they are finalized. I am also talking to friends and associates in some of Nigeria’s blue chip entities to either sponsor our movement or advertise in our magazine. As soon as we begin to monetize Sentinel Nigeria, the contributors will be paid. In the meantime, we ask for their support in terms of quality submissions, and let them accept the exposure we give them and the permanent storage for posterity their works receive in the digital archives of the British Library. Thanks to Internet, these will soon be available to anyone in any part of the world.

Is there any plan to publish the hard copy, given the clamour by literary scholars that there are not much and handy materials for research on new Nigerian writings?

At the moment, there is no plan for a hard copy. The world has actually moved away from the fixation with print journals. The Internet makes research a breeze. Some people worry that many websites seem to disappear after a while with all of its contents. That is true. This is why we subscribe to British Library’s digital archives to preserve our publications. In any case, our international website sentinelpoetry.org.uk has been online since December, 2002 and all our publications are still there intact. We’ve never been offline and do not expect to. Many print journals and even books have appeared and disappeared since then. But we are still standing. Funny thing is, if we invest in publishing a hard copy of the magazine, those scholars will not necessarily buy it or subscribe to it. Lack of support by our literati has been responsible for the death of many Nigerian publications. I believe the wonderful Farafina magazine has been the latest casualty.

You have been outside the country for some time, like many of your colleagues. What has been happening to you in terms of scholarship, writing and the like?

First of all, you must know I am not and cannot be quoted as having referred to myself anywhere as a scholar or intellectual. I am a humble businessman and a facilitator of the arts. Nothing fancy. There was a time I used to delude myself that if it were denied me to write, I would jump off a cliff. But I have not felt like that in over 20 years. My poetry, short fiction, interviews and essays have been widely published in international journals, and I currently have three poetry books on the market, Letter to God and Other Poems, The Bridge Selection: Poems for the Road and Blue Hyacinths which I edited with Geoff Stevens. Time has been my enemy in completing my short story collection, The Magenta Shadow and my interviews collection, On the Record: Collected Interviews with Writers & Artists (2002 – 2009). I have also completed the screenplay of a new film, The Spirit Sword of Justice which will be directed by Obi Emelonye and produced by The Nollywood Factory in association with Eastern Light Entertainment during 2011. All these are secondary in any case. My primary job right now is being a devoted husband to my rock, Thelma Amaka and the very best father I can be to the air in my lungs: my son, Arinze Chinedum, and my daughter, Nwachi Ola.

What’s your take on the recent volte-face by NLNG to flinging its gates open to writers abroad to participate in the coveted prize? How would it influence the quality of the $50,000 prize?

The NLNG Prize has now become a decubitus wound on the butt of Nigerian literature. It is all at once a great, misunderstood, and a totally pointless prize. At first, it appeared to have been designed to encourage home-based writers, but was interpreted by many writers abroad as an exercise in resentment for them.

Now, after last year’s debacle where the prize was not awarded, many writers home and abroad spat on it as a sham and Molara Wood was one of those who called on writers to boycott what she termed a ‘sham.’ I take the view that suddenly deciding now to allow Nigerian writers abroad to participate in the NLNG prize is rude and an insult to writers based in Nigeria. The statement can be paraphrased as, ‘Sorry, no Nigerian writer living in Nigeria can write anything good enough for this prize, let’s try those abroad.’

The prize lacks credibility now, so much that its own mother will not hang its plaque on her wall. I suspect that anyone entering the prize now will not do so for a worthy literary glory, but purely as a financial pursuit. The way my mind works, I will never condemn or judge anyone who wishes to cash in on the prize. I don’t think that winning this discredited prize of $50,000 will take away from the long-term impact of a good book. As a matter of fact, the winner could deploy just ten percent of that sum into promotional activities and laundering the image of his or her work. At the end of the day, whoever chooses to enter work to the NLNG Prize makes a personal decision and we must respect that.

Saturday, September 08, 2012

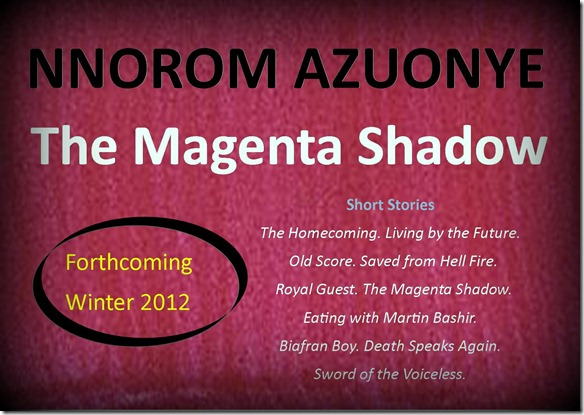

The Magenta Shadow

My collection of short stories due out in December 2012. More details will be made available here in due course.