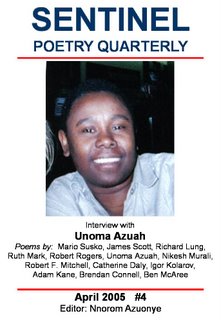

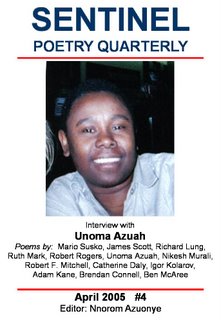

INTERVIEW WITH UNOMA AZUAH

INTERVIEW WITH UNOMA AZUAHBy

Nnorom AzuonyeUnoma Nguemo Azuah is one of the female voices in what is now generally known worldwide as Nigeria’s Third Generation Writers. Author of “Night Songs” (2001), Azuah holds an MFA in Poetry and Fiction from the Virginia Commonwealth University. Formerly editor of The Muse – journal of the English Department, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, she received the Hellman/Hammett Human Rights grant for her writings on women’s issues (1998), and the Leonard Trawick Creative Writing Award (2000). She currently teaches Composition and Creative Writing at Lane College, Jackson, Tennessee, USA. In this interview I attempt to gain more insight into the work of the crop of Nigerian writers of her generation, and also learn a little about her own work.Nnorom Azuonye (NA): What are the thematic burdens and innovations in African or global writing that can be attributed to the ‘3rd generation’ Nigerian writers?

Unoma Azuah (UA): The 3rd generation of Nigerian Writers have had to deal with disillusionment in every aspect of the Nigerian state, especially political. This group transitioned, either as babies or teenagers, from the oil boom of the 70's and 80's to the oil doom of the 90's and 00's. They witnessed the dawn of University closures due to one economic/political upheaval or the other. They witnessed unemployment and have testimonies about the economic and leadership failures of both the military and civilian governments of the country. I also think that these developments as causal effects ushered in the explosion of religious fanatics, churches, crimes, the resort to religious and spiritual quests to cushion the effects - be it in the frenzied cries of pastors, in the novena nights of Catholic masses or even in the ritual killings for money and power. As dark as these may be, they provided rich themes and resources for stories and poems.

Beyond these issues, this generation of writers, the females particularly, have had to question some of the myths and lies our mothers swallowed whole from a rather oppressive patriarchal society. For example, the belief that women had no need to build careers beyond "beds" and "kitchens." This generation of writers have also been able to explore some tabooed topics like sex, and homosexuality.

As for innovations, the Nigerian economic crunch set in motion a mass emigration of Nigerians. When they can not migrate, they are forced to a near existentialist way of examining problems. A good number of their works have given a fair amount of attention to the generation. In fact, it's as if this group of writers have suddenly crashed through the gates of relevance after being ignored for a long while. It's affirming to see these writers grab national and international laurels for their brilliance.

NA: In other words there is no tangible inventiveness in their writing. As you know, excellent examples of existentialist writing can already be found in the works of Sartre, Camus, Nietzsche and Ortega among others. By the way what is innovative about migration to a foreign country?

UA: Migration does not warrant innovativeness per se, but it provides a platform for a more competitive, more diverse and more challenging opportunities to work with the best from all over the world. I would not say that there is no tangible inventiveness in their writing - in fact, there are. Chimamanda Adichie's strength with crafting very graphic details is like no other. Chika Unigwe's wit in creating very moving comic relief in her stories is captivating, and she does it effortlessly. Promise Okekwe's brave and daring efforts at delving into taboo topics like homosexuality is novel. Victor Ehikhamenor's ability to paint a mood and keep a reader reading is also an innovation, mostly because these writers write with a freshness that is unique and rare. These qualities are quite original for me.

NA: In dealing with their disillusionment, have the 3rd generation Nigerian writers merely chronicled and criticised the society's woes, or have they proffered any solutions to heal the society?

UA: In chronicling the pitfalls of our political problems for example, the third generation of Nigerian writers attempt to nudge society to the right direction. I don't think it's a writer's role to prescribe, especially in an imposing manner. I think a writer's role should be more about presenting incidents in such a way that an audience can deduce or take away something from the narrative, and hopefully make a change for the better. In other words, writers/artists are like mirrors; they reflect images, and if you imagine yourself in front of a mirror - the mirror lets you see the awkward hair that needs to be pulled off or the hidden rumple in a blouse. When a writer like Promise Okekwe, in one of her stories for instance, writes about how a promising young man dies in the blaze of the very fuel he hawks in the streets of Lagos - one would hope that such a loss would make people have a rethink. Or that people in charge would try to wipe away poverty and create employment opportunities by focusing less on petroleum and more on areas like agriculture and education.

In addition, when writers like Sola Osofisan and Ike Oguine explore the dilemma of the Nigerian immigrant - the lies attached to the life of living abroad, lies fed by the expectations of people at home, one would hope that these impressions would be corrected, but no.

What makes it worse is that writers are not respected in Nigeria. If they are revered, it is my opinion that corruption would lessen. The leadership would take them more seriously, and somebody like Ken Saro Wiwa would not have been wasted. Therefore, in a community where books, reading and writers are not top priorities for the government, such a society leans on thin hope for the future. Especially in the Nigerian situation, because of hardship and paucity, reading and writing, and buying books have become a luxury; people are too busy trying to survive.

NA: The general view has always been that 3rd generation Nigerian writers focus more on poetry than on other literary genres. Paradoxically, as suggested by Pius Adesanmi1, poetry by writers of this generation has largely been ignored outside Nigeria. He blames limited or non-existent availability of Nigerian books for this. Why else do you reckon the poetry of this generation has not travelled very far?

UA: Things are changing though, thanks to the World Wide Web and some international scholars. Somebody like Ishmael Reed is assisting with, not just the spreading of their poetry, but their writing generally, I think. A few years ago he published an anthology of poems entitled "25 New Nigerian Poets," which was edited by Toyin Adewale-Gabriel. The book got a fair review in the US. And some of these writers have also published their poems in international anthologies. However, poor circulation and limited availability of these books, as Pius said, are the main reasons why the poems of this generation have not travelled too far. In due time, most of these poems will go far and wide, I believe.

NA: You don't reckon then that perhaps the international poetry reading publics have found some of the Nigerian portraits of disillusion irrelevant? More so, as some Nigerian critics have often suggested that in many poems by the generation in question, political or social activism was sublimated over form or craft.

UA: I don't think so. There is a possibility that they can't identify with the quagmire of political subjects. Or, even that they don't understand most of the Nigerian expressions. But I don't agree that it's an issue of relevance. For instance, in Anderson Tepper's review of "25 New Nigerian Poets,” in the Voice Literary Supplement, he acknowledges the overriding political despair in the collection. What he, on the other hand, finds puzzling are some of the terms. He attests to this when he writes that "Even with a glossary at the back to help with traditional Igbo and Yoruba terms, some of these poems can leave you scratching your head over their meaning...." Now, he could be referring to some of the weaknesses in the individual poems; maybe disjointed use of metaphors, etc. But beyond this, I have the impression that some international readers of Nigerian poetry expect to be fed in plain English laced with Western terms. All some of these readers need to do is research. As a student at Nsukka I know that British Literature was practically crammed down my throat. I had to do the extra work of finding out what certain British terms meant. Many a time as a growing child in Nigeria, I dreamt of White Christmas even before I saw snow.

Anyhow, dominant political issues or social activism does not take away from our craft and the general aesthetics of our poetry. I don't think so. South Africa, for example, saw the cropping up of many works addressing the brutality of the apartheid system. It was a dominant theme in most of their writing. I don't think they alienated foreign readers in the process. The point remains that South Africa had and still have a better means of circulating their books internationally mostly because their government ranks literature high in their list of priorities, I think.

NA: It is fair enough to suggest that non-Nigerian readers of Nigerian literature should research into the things that confound them. But what is the state of the Nigerian information resource and retrieval system that should make such research possible? Are Nigerian scholars studying their own writers enough and providing study guides?

UA: Again this issue is very much connected to the state of the Nigerian economy, or lack of the Nigerian governments’ commitment to education. At the risk of sounding like a broken record, most Universities in Nigeria are in a terrible shape now. There are no substantial amounts of money provided for research, for example. God! the professors themselves are underpaid. During my recent visit to my alma mater—the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, I was moved to tears. UNN is a shadow of itself. The buildings are dilapidated; the vibrancy that existed in the 80’s is gone. This prevailing gloom does affect scholarship. On a further instance, a journal like OKIKE was for a long time out of circulation, if it is still not out of circulation, because of lack of funds. OKIKE is an exemplary journal, mainly as an outlet for our scholars studying our Literature, but when resourceful projects like this lack funding, how else can vivacious scholarship about Nigerian Literature be sustained? On the other hand, scholars like Pius Adesanmi, Remi Raji, Ezenwa Ohaeto, Akachi Ezeigbo, Mary Kolawale, Obioma Nnaemaka and others have been quite aggressive and prolific with providing materials that are accessible to the international readers of Nigerian literature. Definitely, more needs to be done. Nevertheless, keen researchers can find a good amount of materials on Nigerian Literature, chiefly with the explosion of information on the internet, I think.

NA: You have published both fiction and poetry. Which of these genres are you more comfortable with and why?

UA: I am comfortable with both, but I am more excited about poetry than fiction. This is because I love the urgency in poetry, the poignant use of words, the economy of words, the apt images and metaphors that say it all. What one can say in a stanza of a poem could take more than fifty pages to be re-enacted in fiction. I don't think I have the patience for longer narratives, even though it became one of the challenges I decided to take up in graduate school. My first attempt at a very long narrative is with my novel, "Sky-high Flames," which would be released before the end of this year. The experience of writing it has left me with a mixed feeling. It is an adventure worth taking though. Working on the book forced me to imbibe the kind of discipline and patience I didn't apply myself to in the past. The experience made me feel as if I have stumbled upon a formula. I realised that some of my short stories can be turned into novels if I expand the conflicts, scenes and characters. So, who knows, maybe I would come up with more novels in time to come. It was also wonderful to discover how far I could stretch my imagination over a vast span of landscape. In all though, and with the cliché some men may use, poetry is my mistress, and fiction is my wife.

NA: Good to learn about "Sky-high Flames"2 Hopefully it will enjoy the same international interest as Abani's "Graceland", Adichie's "Purple Hibiscus" and Atta's "Everything Good Will Come." Back to poetry, Unoma. You've already mentioned some of the general issues that concern writers of your generation. On what peculiar themes do you anchor your own poetry?

UA: I explore a variety of themes. I am not fixed on any specific theme per se. However, I am moved often to identify with the underprivileged and the oppressed. Perhaps I do habitually focus on sexuality and sexual minorities, the mentally challenged, the rejects of society, etc. because the pain and burden these group of people stomach, I share and identify with as a human. Another topic I enjoy writing about is religion. For example the Catholic in me still feeds the poet in me. One of the things I examine sometimes is the extremity that can come out of our religious experiences as people still torn between our alien religion and our traditional beliefs. So, sometimes, I look at the futility of unbelief and faith. Sometimes, I also study the benefits of faith, etc. African traditional religion is another aspect I search. For instance, I consciously try to create a space for the goddesses of my traditional religious inheritance. The conflicts that exist between the two are often the one thing I attempt to resolve.

I can get quite pre-occupied with political and economic issues that threaten the Nigerian citizenry. On a brighter side though, I work often too on the theme of love, liberation and empowerment.

There are of course other things that can be considered mundane; the comic in an unexpected fall, dressing modes, a banter with friends, a bundle of flapping papers, etc. Further, a market scene can be an inspiration for a humorous poem. A night club scene too, can offer reasons for a poem. So materials come from diverse situations and places.

NA: By the way, why is it that like you, many Nigerian poets living outside the country still locate the bulk of their work in Nigeria, many times writing out of memory? What is the harm in examining life in their current environments?

UA: A good number of Nigerian poets living abroad were born in Nigeria and mostly left Nigeria as adults. It is difficult to pull away from where one is rooted and begin to hub on a new environment immediately. The shock of the huge change, and some of the drastic transformations hit you like a bolt, and it's as if you can't help but hold on to the only thing you've known, therefore you go into your inner recesses for security. That core is basically all that you came with as an African or a Nigerian. In fact, we then have a tendency to become pro-home. The cultural shock may seem subtle at first but it does go deeper than it seems. So, even though we live and work here, our worldview is still very much anchored at home. I know that even after six years of living in America I was not able to write a poem set in America. The one poem I eventually wrote that is set in Cleveland, Ohio was based on the trauma of experiencing winter straight from Nigeria. At 80 degrees in a warm American summer I was shivering. The poem was not written as soon as winter hit, it came a few years after that experience. It does take us a while to process the overwhelming wave that comes with a new environment and to feel comfortable enough to feature such in our poems. That is, if we process it at all. However, with time, probably after a long while some poets do begin to acknowledge their new environment.

NA: Understandably the bleakness in the writings of your generation represents your contemporary reality back in Nigeria and of course immigrant experiences in foreign lands. Do you sometimes exhume the magic and innocence of your childhood in your own poetry as a way of shining a light of hope on the everyday trials of adult life?

UA: Yes, of course! The skies are not always blacked out. Like seasons, the sun does stretch its strands of rays to us. In my collection of poems, Night Songs, for instance, I do celebrate blissful memories of childhood, especially in poems like "Umunede", "Rain Rampage", and "Nsukka", to an extent. Further, I do eulogize dance in "Drum Dance". I celebrate love in "Flames", "The Storm You Are", and the fun of night life in Nigeria, in "Live Band in Port Harcourt." Poets like Nike Adesuyi, Angela Agali-Nwosu, Uche Nduka, Chiedu Ezeanah, Lola Shoneyin and others, also celebrate varied themes that are not always overcast. For example, Ezeanah in his "July Rain", and "Split Song”, extols love. Uche Nduka in his latest collection, "If Only the Night", commemorates life in exile as well as love.

NA: One last thing. Tell me a little about your writing habits, sources of inspiration and style influences. I’d like to know as well about your personal all time favourite book of poetry.

UA: I have very irregular writing habits. I used to be one of those who would wait for inspiration to come, until I realised that the truism, "Writing is 99 percent perspiration and 1 percent inspiration," also applies to me and everyone else. That realisation didn't really make me develop a disciplined writing habit, but it did/does make me sit and write as often as I can, especially at night. Writing residencies have as well helped me come up with more works that I may not have been able to create if I didn't get them. They provide such isolation that one is forced to do something. Conversely, one of the poems I wrote during the last residency I had dealt with the discomfort of seclusion. This stanza from the light-hearted poem, "Eureka Spring" I think, demonstrates the kind of gripe I sometimes have during a writing seclusion:

The ghosts of writers dead and gone kept me all awake

The silence, so dense like a wall, makes me want to scream

But I have a crow perched on my back chirping all away.

A crow kept me company today at the Harmon Park

Even though the serene environment comes in quite handy for inspiration and perspiration, I was grateful for the company of a crow.

As for influences, I don't quite remember who and at what point some writers I read and studied made huge impact on me, but writers like U'Tamsi, David Diop, Awoonor, Ifi Amadiume, Sonia Sanchez, Alice Walker, Audre Lorde, Masizi Kunene, Sylvia Plath, Emily Dickinson, Jane Coetez, Yousef Koumouyaka, Hafiz and Li Yung Lee, etc. are some that I remember. For their use of folklore, political defiance, the surreal, stacks of metaphors/images and for the intense burst of life in their works.

Hummm, my personal all time book of poetry…. That is a hard one because I can't readily pick one as my all time best. I know that a number of Sylvia Plath's like "Ariel," and "Crossing the Water," are some of the books that are like fixtures on my shelf. In addition is Audre Lorde's "Collected Poems." Very recently too, I have been enjoying Rita Dove's "Beulah" and Kevin Young's "Black Maria," particularly because of the way they make the familiar so fresh and mystical.

1. “Nigeria’s Third generation poetry, canonization, and the north American academy: Random Reflections” Adesanmi, Pius (Sentinel Poetry Quarterly, January 2005, #3).

2. Sky-High Flames – the novel by Unoma Azuah has now been released by Publish America www.publishamerica.com

“Interview with Unoma Azuah” by Nnorom Azuonye was first published in Sentinel Poetry Quarterly April 2005 #4. www.sentinelpoetry.org.uk Copyright: Nnorom Azuonye and Unoma Azuah 2005. All Rights Reserved.